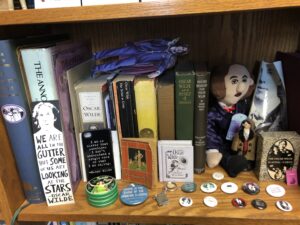

A bookshelf of Wilde-related paraphernalia

Professor of English Chris Foss presented a paper entitled “ ‘The secret of life is suffering’: Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis as Hard Times Survival Guide” on Sun. Oct. 8th at The Victorians Institute’s Annual Conference in Raleigh, North Carolina. In the paper Foss argued that (as an analysis of De Profundis, his tour de force letter written in Reading Gaol so powerfully relates) Wilde’s prison experience ultimately serves to bring his former life as a prince of pleasure “into harmony with the wounded, broken, and great heart of the world.” In spite of (or, rather, more accurately, because of) the bodily debilitation and psychological distress he endures while incarcerated, such hard times increase his appreciation for the beauty and value of those lives dominated by difficulty, convincing Wilde to champion as his own chosen confraternity in the few years remaining to him persons variously marginalized and/or pilloried by society.